Your Guide to NZ Marine VHF Channels: The Essential On-Water Companion

Understanding one of the most crucial pieces of equipment on your boat—the marine VHF radio—is essential for any Kiwi mariner. This isn't merely a gadget; it's your primary, legally recognised lifeline for safety and communication out on the water. This guide provides a clear overview of the New Zealand VHF system, from making life-saving emergency calls to everyday communication with marinas and other vessels.

Your Lifeline at Sea: Getting to Grips with NZ VHF Radio

A Very High Frequency (VHF) radio is the cornerstone of maritime communication, forming a purpose-built network that connects you to other boats and, most importantly, to shore-based assistance. Once you lose mobile reception—which is common along New Zealand's coastline—your VHF is often the only reliable way to call for help. Its importance in marine safety cannot be overstated.

Understanding the specific marine VHF channels NZ boaties are required to use is the first, most critical step. These channels function like lanes on a motorway; each has a designated purpose. You wouldn't stop in the fast lane to ask for directions, and similarly, you don't use the emergency channel for a casual chat. Using the wrong channel can obstruct the network and, critically, prevent a genuine emergency call from being heard.

More Than Just Emergencies: The VHF in Day-to-Day Boating

Beyond worst-case scenarios, your VHF is an incredibly practical tool for everyday life on the water. It is a legal communication device commonly used throughout New Zealand for tasks such as:

- Filing Trip Reports: Logging your trip details with Coastguard Radio is a simple, effective safety measure that ensures someone knows your location and expected return time.

- Getting Weather Updates: Dedicated channels broadcast continuous marine weather forecasts. This is essential information for making safe decisions about your passage.

- Contacting Marinas and Bridges: The VHF is the standard method for arranging a berth for the night, a spot at the fuel jetty, or requesting a bridge lift.

- Chatting with Other Boats: It's the primary way to communicate with other vessels, whether you're coordinating a fishing spot with a friend or warning others about a navigational hazard.

For any Kiwi out on the water, mastering the VHF isn't just a good idea—it's a fundamental skill. It connects you directly to a massive safety network and the wider boating community. It’s what ensures that no matter where you are along our incredible coastline, you're never truly on your own.

To help you get started immediately, here’s a quick-reference table covering the essential channels every boater in New Zealand must know before leaving the dock.

Quick Reference: Critical NZ VHF Channels

This table breaks down the most important channels you'll use. Take a moment to familiarise yourself with them—better yet, print a copy and keep it at the helm.

| Channel | Primary Use | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| 16 | Distress, Safety, and Calling | This is the most critical channel. It is monitored 24/7 for Mayday (distress), Pan Pan (urgency), and Sécurité (safety) calls. Use it to make initial contact with another vessel before switching to a working channel. |

| 67 | Maritime NZ Continuous Weather | Tune in here for continuous, automated weather forecasts and warnings for your specific area. An absolute must for planning your day. |

| 73 | Coastguard New Zealand (Working) | This is Coastguard's main working channel for routine communications like logging trip reports, requesting a radio check, or non-urgent assistance. You'll usually be told to switch to this channel after calling them on 16. |

| 06 | Ship-to-Ship Safety and SAR | Primarily for safety-related communication between boats. It's also the dedicated channel used to coordinate on-water Search and Rescue (SAR) operations between ships, aircraft, and Coastguard. |

Knowing these four channels is the foundation of safe and effective radio use. Committing them to memory is your first and most important step.

Why We Have Marine Radio Rules in New Zealand

To fully appreciate the structured system of marine VHF channels NZ boaties depend on, it's helpful to understand its origins. Before clear rules were established, the airwaves were a chaotic free-for-all, making reliable communication nearly impossible, especially in life-threatening situations. The system we have today was born out of necessity and shaped by historical disasters that demonstrated the deadly cost of disorder at sea.

Imagine the radio spectrum as a busy motorway with no lanes, speed limits, or rules. That's what early maritime radio was like. This had to change when governments globally realised that to save lives, the airwaves needed structure and control.

From Chaos to Order on the Airwaves

Early in the last century, a series of maritime disasters highlighted a major weakness in global shipping: the lack of standard safety protocols. Without a dedicated channel for distress calls, a ship in trouble was essentially shouting into a void. Their desperate pleas for help could be lost in casual chatter or go unheard by anyone listening on a different frequency.

The sinking of the Titanic in 1912 was a global wake-up call, but New Zealand was already taking action. The NZ Government began establishing marine radio coast stations in 1911, a move that proved tragically timely. That event and others like it underscored the urgent need for a universal distress channel that all large vessels had to monitor. You can learn more about how these radio services evolved in NZ history.

This led to a fundamental change in how we view radio waves. The spectrum was finally recognised as a finite public resource, similar to land or water. It could not be a free-for-all; it had to be managed carefully to serve the public good, with safety as the absolute top priority.

The core principle is simple: a distress call must always get through. Every rule, every channel designation, and every licence requirement is built around this one non-negotiable fact. When you hear a Mayday call, everything else stops.

Why Licensing Is Essential

This is precisely why we have a licensing framework for VHF radios. By ensuring operators are certified and vessels have a unique callsign, the system confirms that everyone on the airwaves knows the rules. This prevents the system from becoming useless through overuse and misuse—a classic "tragedy of the commons" scenario.

This regulated approach is designed to:

- Prevent Interference: By assigning specific jobs to specific frequencies, it stops vital communications like weather broadcasts or port operations from being drowned out by chatter.

- Ensure Interoperability: Standardised channels mean a boater from Bluff can communicate with a vessel in the Bay of Islands or even a passing international ship without issue.

- Prioritise Safety: Most importantly, it keeps Channel 16 and other key safety frequencies clear for their sole purpose—saving lives.

The organised structure of marine VHF channels NZ uses today is the direct result of these hard-earned lessons. It’s a system designed to turn a simple radio into your most powerful lifeline when you need it most.

Navigating the Complete NZ VHF Channel List

Once you’re comfortable with the core safety channels, a truly confident skipper knows how to use the full spectrum of frequencies. Think of your VHF radio's channel list as a toolkit; using the right tool for the right job makes every task smoother and, most importantly, safer. Knowing the full list of marine VHF channels NZ uses means you can communicate effectively without clogging up critical safety or operational traffic.

This guide will give you a mental map of what your VHF can do, from simple ship-to-shore calls to picking up vital weather broadcasts. Understanding which channel to flick to for a specific task is a massive part of good seamanship.

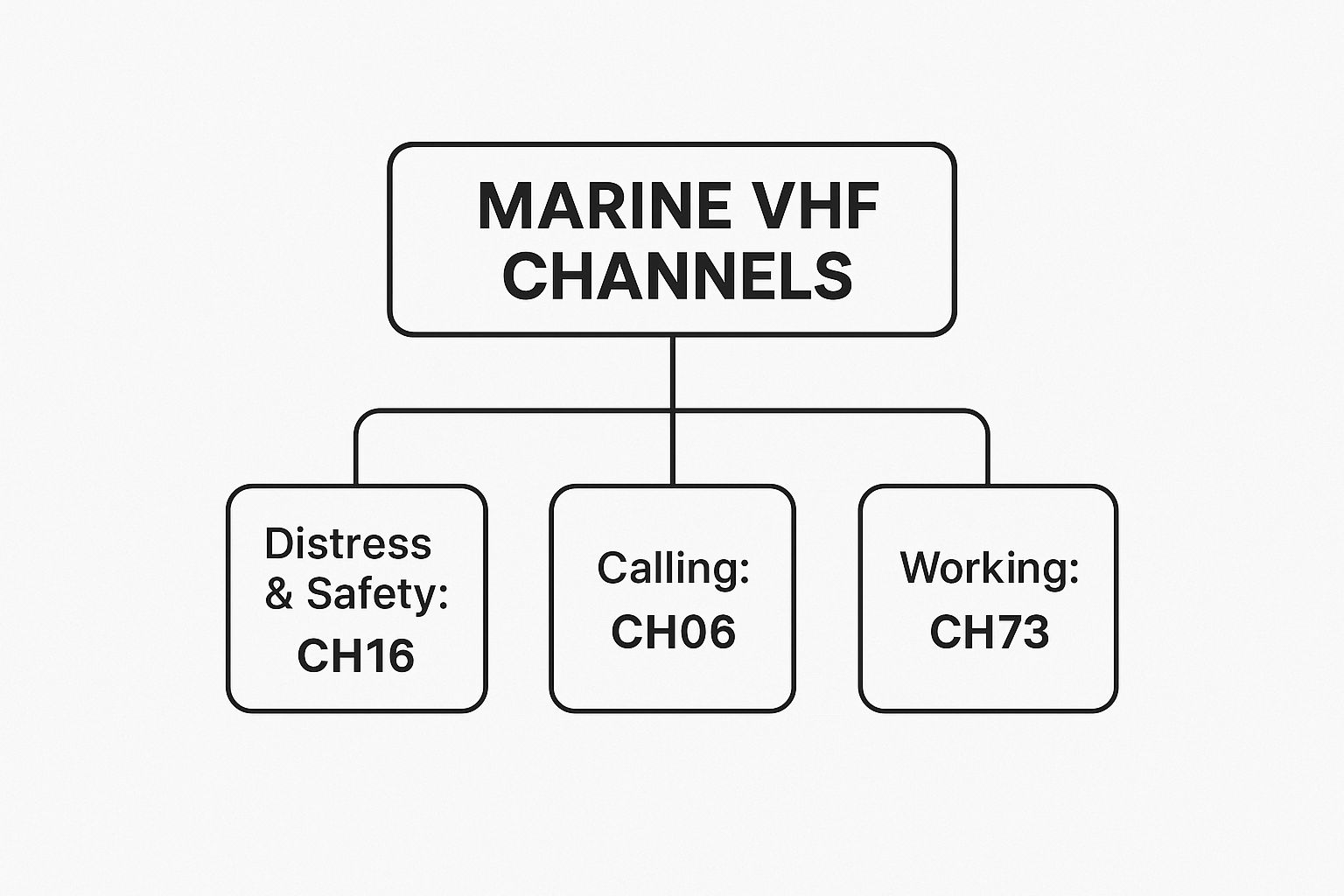

This simple infographic helps break down the hierarchy for the most common channel types, making it easier to remember what each one is primarily for.

As you can see, it clearly separates the absolute priority of Channel 16 for distress calls from the hailing function of channels like 06, and the day-to-day chatter handled on channels like 73. This reinforces the whole idea of designated channels for specific jobs.

Understanding Simplex and Duplex Channels

Before we jump into the full list, there’s a key technical difference you need to get your head around: simplex versus duplex operation. This one detail completely changes how a conversation on any given channel works.

-

Simplex Channels: These use a single frequency for both talking and listening. It’s just like a walkie-talkie—only one person can talk at a time. When you press that transmit button, everyone else on that channel is in listening mode. Most boat-to-boat comms happen on simplex channels.

-

Duplex Channels: These clever channels use two separate frequencies—one for transmitting and one for receiving. This allows for a real-time, two-way conversation, just like a phone call. You’ll find these are mainly used for talking to shore-based stations like Maritime Radio or your local marina, as they rely on powerful repeater towers.

Knowing the difference isn't just theory; it's practical. If you're on a simplex channel (like 06 or 72), you absolutely have to wait for the other person to finish and say "over" before you can reply. Jump in too early, and you'll just be talking over them. On a duplex channel (like your marina's working channel), you can have a much more natural, back-and-forth chat.

The Full List of NZ Marine VHF Channels and Their Uses

Here’s a comprehensive look at the channels you'll be using in New Zealand waters. Getting familiar with what each one is for is a great way to become truly fluent with your radio. For an even deeper dive, you can also check out our extended article on VHF marine radio usage in New Zealand.

Here is a table laying out all the channels, what they're for, and how they operate.

Comprehensive NZ Marine VHF Channels and Uses

| Channel Number | Designated Use | Communication Type | Key Operator/Service |

|---|---|---|---|

| 01, 02, 04, 05 | Port Operations (Working) | Simplex/Duplex | Port Companies, Harbourmasters |

| 06, 08 | Inter-ship (Boat-to-Boat) | Simplex | Recreational & Commercial Vessels |

| 10, 11, 12, 14 | Port Operations (Working) | Simplex | Port Companies, Tugboats |

| 13 | Inter-ship Navigation Safety | Simplex | All Vessels (Bridge-to-Bridge) |

| 16 | Distress, Urgency, Safety & Calling | Simplex | All Vessels, Coastguard, Maritime NZ |

| 17 | Inter-ship (Low Power Only) | Simplex | All Vessels (1-watt maximum) |

| 19, 20, 21 | Continuous Weather | Duplex | Maritime NZ / MetService |

| 60, 61, 62, 63 | Coastguard (Working) | Duplex | Coastguard New Zealand |

| 65, 66 | Coastguard (Working) | Duplex | Coastguard New Zealand |

| 67 | Maritime Safety Information (MSI) | Simplex | Maritime NZ (Primary Weather) |

| 72, 77 | Inter-ship (Non-commercial) | Simplex | Recreational Vessels |

| 73 | Coastguard (Working) | Simplex | Coastguard New Zealand (Primary) |

| 80, 81, 82, 83 | Marinas / Slipways | Duplex | Marina Operators |

| 84, 85, 86 | Special Event / Yacht Clubs | Simplex/Duplex | Race Committees, Event Organisers |

This detailed list gives you the power to pick the right channel for any situation, making sure your transmissions are both legal and effective. By respecting these designations, you're doing your part to keep our maritime radio environment orderly and safe for everyone on the water.

How New Zealand's VHF Network Keeps You Safe

Your VHF radio is a powerful piece of kit, but its real magic comes from the vast shore-based network it connects to. This robust system, managed by Maritime New Zealand, elevates your radio from a simple boat-to-boat gadget into a genuine lifeline. It's the reason someone is always listening.

At its core, the system is a massive web of coastal stations, all strategically placed to blanket New Zealand’s sprawling coastline. The Maritime New Zealand VHF network is made up of 28 coastal stations covering the mainland, plus another two keeping watch over the Chatham Islands.

These stations all monitor VHF Channel 16 (156.8 MHz) around the clock. This channel is strictly for distress, safety, and initial calls, and that constant monitoring is the system's most critical job. It guarantees that a Mayday call will be heard and acted on, no matter the time of day or night.

Broadcasting Safety to All Mariners

But the network does more than just listen for trouble; it actively broadcasts vital information to help you stay out of it. This is called Maritime Safety Information (MSI), and paying attention to it is a fundamental part of good seamanship.

MSI broadcasts deliver crucial updates that can directly shape your decisions on the water:

- Weather Alerts: From sudden gale warnings to nasty sea state updates, these give you the heads-up you need to seek shelter or alter course before conditions turn ugly.

- Navigational Warnings: This could be anything from a newly found submerged rock to a channel marker that’s gone adrift or a heads-up about a temporary exclusion zone for a race.

- Urgency and Safety Messages: If a vessel is overdue or another urgent situation is unfolding, the network relays this information to all boaties in the area.

By tuning into these broadcasts on the designated channels, you’re giving yourself the best, most current picture of what's happening out there.

Think of the VHF network as your eyes and ears over the horizon. It's an invisible safety net that extends far beyond your own line of sight, plugging you into a coordinated national response system.

Understanding the Network's Limitations

While the coverage is impressive, you've got to be realistic about its limits. VHF radio works on a 'line-of-sight' basis, meaning the signal travels in a relatively straight line. In a country with as much rugged coastline as New Zealand, that can be a problem.

Towering cliffs, deep sounds, and remote islands can all create signal "shadows" or black spots where communication is patchy at best, or completely impossible. You simply can't assume you'll have a clear line to a shore station in places like Fiordland or along the more isolated parts of the West Coast.

Although your VHF is a cornerstone of marine safety, a smart skipper knows it's just one part of the puzzle. A truly effective plan involves a more comprehensive emergency preparedness checklist that covers all the bases, especially if you're heading somewhere remote.

For boaties venturing far offshore or into those known black spots, having a legal backup for communication isn't just a good idea—it's essential. This is where other technologies become crucial:

- MF/HF Radio (SSB): The go-to for true long-range, over-the-horizon communication.

- Satellite Phones: Give you a reliable voice link from almost anywhere on the planet.

- PLBs or EPIRBs: These send a distress signal directly to rescue authorities via satellite.

By understanding both the incredible reach and the very real limits of the VHF network, you can make smarter, safer decisions on the water. For a deeper dive into all the options, check out our guide on choosing the right marine radio for NZ conditions.

Proper VHF Radio Use and On-Water Etiquette

Knowing the list of marine VHF channels NZ provides is one thing, but actually using your radio with confidence is a different skill altogether. Good radio etiquette isn't just about being polite on the water; it's about keeping the airwaves clear, efficient, and ready for the moment someone truly needs them. Think of it as the on-water version of good road manners.

The single most important rule is to listen before you transmit. Seriously. Before your hand even goes near the transmit button, listen to the channel for at least 30 seconds. Make sure it's not already in use. Jumping into someone else's chat is just bad form, but interrupting an urgent call could be disastrous.

Making a Standard Call

When you need to get in touch with another boat for a routine chat, there's an internationally recognised way to do it. Following the procedure keeps things quick, clear, and professional.

Let’s imagine your boat, Blue Duck, needs to contact Mary Jane. Here’s how it plays out:

- Pick the Right Channel: You'll start on a designated calling channel, which in New Zealand is almost always Channel 16. Never use a working channel to hail another boat for the first time.

- Start the Call: Clearly state the name of the vessel you're calling (twice is good practice), followed by your own vessel's name. It sounds like this: "Mary Jane, Mary Jane, this is Blue Duck."

- Wait for their Reply: The other skipper will acknowledge your call and tell you which working channel to move to. For example: "Blue Duck, this is Mary Jane. Switch to channel 72."

- Acknowledge and Switch: All you need to do is confirm you got the message and then change your radio to the new channel. A simple "72" is all that's needed.

- Have Your Chat: Once you're both on the new working channel, you can have your conversation. Just remember to keep it brief and to the point—these channels are a shared resource.

Using your vessel’s callsign isn't just a suggestion; it’s a required part of the procedure that properly identifies you on the network.

The Three Prowords You Must Know

Procedural words, or "prowords," are the universal language of maritime safety. Knowing what they mean—both when to use them and how to react when you hear them—is a non-negotiable part of being a responsible skipper.

- MAYDAY: This is the big one. It's the highest-level distress call, reserved for situations where a vessel or person is in grave and imminent danger and needs immediate help. Think fire, sinking, or a life-threatening medical emergency.

- PAN PAN: This is an urgency signal. It means there’s a serious situation that isn't life-threatening yet, but could easily become so if it's not dealt with. Engine failure in a busy shipping lane, losing your steering, or a non-critical medical issue are all classic Pan Pan scenarios.

- SÉCURITÉ: (Pronounced 'say-cure-it-tay'). This is a safety signal. Skippers and coast stations use it to broadcast important information about navigational hazards or weather. You'll hear this for things like floating logs, unlit buoys, or warnings about incoming severe weather.

When you hear a Mayday call, you must immediately cease any transmission and listen. Your silence is critical. You might be the only one who heard the call, or you may be in a position to render assistance, and the last thing rescuers need is interference.

Radio Checks and Power Settings

Getting a radio check is a great way to make sure your gear is working, but never use Channel 16 for it. Clogging up the most important channel on your radio is a serious no-no. Instead, call Coastguard Radio on a local working channel (like 62 or 73, depending on your area) and politely ask for a radio check.

Finally, get to know your power settings. Your VHF has two modes: low power (1 watt) for talking to boats nearby and high power (25 watts) for reaching out over long distances. Using high power to chat with the boat in the next bay is like shouting at someone standing right next to you—it’s totally unnecessary and can bleed over and disrupt conversations miles away.

Always default to low power unless you genuinely need the range. It's a simple act that marks you as a considerate and experienced mariner.

Getting Legal With Your VHF Licence and Callsign

Using a marine VHF radio in New Zealand waters is more than just flipping a switch. It comes with some serious responsibilities, and for good reason. These rules aren't just bureaucracy; they're in place to protect the entire maritime safety network. When you or another boatie needs help, you need to know that system will work perfectly.

You’ve got two key legal hoops to jump through: getting your radio operator certificate and registering a unique callsign for your boat. It’s a lot like driving a car. Your operator certificate is your driver's licence, proving you know the rules of the road. Your callsign is your vessel's number plate, identifying you on the water. Both are non-negotiable for staying safe and legal on our marine "highways."

Getting Your Operator Certificate

Here in New Zealand, anyone operating a marine VHF—whether it's fixed to the console or a handheld unit—must hold a Maritime VHF Radio Operator Certificate. There are no exceptions. This certificate is your proof that you have the skills to use the radio properly, particularly when things go wrong.

The good news is that getting certified is a pretty straightforward process. It usually involves a short, accessible course designed to make sure every operator is competent and confident.

What you'll learn in the course:

- Correct Calling Procedures: How to properly hail another vessel or a shore station without causing a fuss.

- Distress and Urgency Calls: Mastering the right words and procedures for Mayday and Pan Pan calls.

- Channel Knowledge: Getting to grips with the specific jobs of the different marine VHF channels NZ boaties use.

- Everyday Operations: The basics of logging trip reports, grabbing weather updates, and doing a proper radio check.

You can find courses run by approved providers, like Coastguard Boating Education, all over the country. Once you complete the course and pass a simple exam, you'll have the certificate you need to get on the air legally.

Your radio operator certificate isn't just a bit of paper. It's your commitment to the safety of everyone on the water. It ensures you know exactly what to do—and what not to do—when it counts, keeping those vital emergency channels clear and effective.

Securing Your Vessel's Callsign

The second piece of the legal puzzle is getting a unique callsign for your boat. Think about it: no two cars have the same registration plate, and it’s the same on the water. This unique ID is absolutely vital for search and rescue, as it connects your vessel directly to your contact details.

Getting a callsign is a simple administrative task handled by Radio Spectrum Management (RSM), which is part of MBIE. You can usually do it all online by providing a few details about your vessel.

Once it's issued, this callsign becomes your boat’s official identity on the airwaves. You're required by law to use it every time you make a call, which helps Coastguard, Maritime NZ, and other boats know exactly who you are. Ticking these legal boxes is a fundamental part of being a responsible boatie in Aotearoa, making sure our airwaves remain an orderly, life-saving resource for us all.

Right, let's dive into some of the questions we hear all the time from Kiwi boaties about their VHF radios. Getting your head around the rules and the tech can feel a bit daunting, but it's actually pretty straightforward once you break it down.

Here are some clear, simple answers to help you get out on the water with total confidence.

Core Legal and Technical Questions

Do I really need a licence to use a handheld VHF in NZ? Yes, you absolutely do. It doesn't matter if it's a fixed unit bolted to the dash or a handheld you can carry around – if you're operating a marine VHF radio in New Zealand, you legally need a Maritime VHF Radio Operator Certificate.

It might seem like a bit of a hassle, but it's all about safety. This rule ensures everyone on the airwaves knows the right way to call for help and how to use the radio without causing problems for others. It’s a vital piece of the safety puzzle for every single person out on the water.

What's the difference between a simplex and a duplex channel? This is a great question. Think of it like this: a simplex channel is like a walkie-talkie. It uses just one frequency, so only one person can talk at a time. You press the button, you talk; you let go, you listen.

A duplex channel is more like a phone call. It cleverly uses two frequencies at once, letting both people talk and listen at the same time. Most of your everyday boat-to-boat chats will happen on simplex channels, while duplex is typically reserved for calls to a marina or Maritime Radio.

On-Water Usage and Best Practices

Can I use my VHF to chat with friends on another boat? You can, but there are a couple of ground rules. For quick, practical chats with another boat – say, to coordinate where you're heading for lunch – you need to use the designated 'inter-ship' or 'non-commercial' channels. In New Zealand, these are channels 06, 08, 72, and 77.

The golden rule is to keep it short and sweet. Never, ever use Channel 16 or other busy working channels for a casual natter.

The airwaves are a shared resource, a bit like a single-lane bridge. Keeping your conversations brief and to the point ensures the channel stays clear for urgent safety messages or important operational calls.

How far will my VHF signal actually travel? This is the classic "how long is a piece of string?" question, because VHF is a 'line-of-sight' technology. The single biggest factor is the height of your antenna.

From a typical small boat, you can realistically expect a range of about 5-10 nautical miles when talking to another small boat. If you're calling a shore station with a big antenna on a hill, that range can easily stretch out to 20 nautical miles or even more. Just remember that big cliffs, headlands, and islands will block your signal and reduce that range significantly.

For a deeper dive into other common questions, feel free to check out our full list of frequently asked questions.

At Mobile Systems Limited, we specialise in providing robust, reliable marine communication solutions that stand up to New Zealand's demanding conditions. From high-performance Icom VHF radios to custom network installations, our expert team ensures you have the right gear to stay safe and connected. Explore our full range of marine electronics at https://mobilesystems.nz.