Lone Worker Safety: A Guide to Legal Devices & Solutions in NZ

Keeping your people safe when they're working alone isn't just good practice—it's a legal and moral responsibility for every New Zealand employer. This means shifting from a reactive mindset to one of proactive risk management. It’s about more than just ticking boxes; it's about genuinely protecting your team with the right communication devices and solutions for the unique dangers they face in isolation.

Your Obligations for Lone Worker Safety in NZ

If you have staff working by themselves, understanding your legal duties is the first step. This is about safeguarding your people, whether they're a community healthcare worker visiting a new client's home or a contractor on a remote farm. In these situations, reliable communication isn't a luxury; it's a legal necessity.

Working alone is common and legal in New Zealand, but it comes with serious safety considerations that you, as the employer, must manage.

The Health and Safety at Work Act 2015 (HSWA) is the cornerstone of this responsibility. It mandates that businesses must carry out detailed risk assessments for all lone working situations. The goal? To identify hazards before they cause harm and implement effective controls, including reliable communication solutions, to manage them.

Understanding "Reasonably Practicable"

The HSWA revolves around a central idea: taking all steps that are 'reasonably practicable' to manage health and safety risks. This simply means you must do what's reasonable to protect your workers, weighing up the likelihood and severity of potential harm against the availability and cost of ways to fix it.

Here’s a look at the official wording from the Health and Safety at Work Act 2015 that lays out this fundamental duty.

This legal text makes it crystal clear: every business has a primary duty of care to ensure worker safety, so far as is reasonably practicable. For lone workers, this responsibility is amplified. Their isolation can turn a minor accident into a life-threatening emergency, making reliable communication a critical control measure.

A proactive safety plan, built around dependable communication, is your best defence. Waiting for an incident to happen is a failure of this primary duty of care. The goal is to anticipate challenges—from communication blackspots to emergency response delays—and build a system that prevents them.

Real-World Risks in New Zealand Industries

The dangers lone workers face are incredibly varied, depending on their role and environment. A security guard doing night patrols faces different threats to a technician servicing equipment in an area with potentially explosive atmospheres. In these hazardous zones, you cannot compromise on equipment.

For a deeper dive into this specific area, have a look at our comprehensive guide to intrinsically safe portable radios, which are an absolute necessity for these high-risk environments.

Consider these common Kiwi scenarios:

- Agriculture: A farmer is working alone in a back paddock with no mobile reception. They could have a medical event or get injured by machinery, miles from help. A satellite messenger or PLB is essential.

- Healthcare: A district nurse might encounter an aggressive patient during a home visit with no immediate backup. A discreet personal alarm with GPS tracking provides a lifeline.

- Forestry: A surveyor working deep in a remote forest could slip and fall, unable to walk out. Reliable two-way radio or satellite communication is their only connection to rescue.

In every one of these cases, having a reliable communication device and a clear emergency plan is a fundamental part of meeting your legal obligations under the HSWA.

How to Conduct a Lone Worker Risk Assessment

Let's move from the legal framework to the practical foundation of your safety plan: a proper risk assessment. This isn't a box-ticking exercise. It's a living process that identifies the real-world dangers your people face when they’re out on their own, and it directly informs your choice of safety devices.

The aim is to get specific. We need to move past generic risks and dig into the hazards unique to your operations. Imagine a technician sent to a remote pump station—what happens if there's no mobile signal? That's a huge risk that demands a satellite-based solution. Or think about a community health worker; their biggest threat might be aggression, requiring a discreet alarm.

A thorough assessment turns your safety policy from a dusty document into a practical tool that actively reduces risk. It helps you get ahead of problems, whether that's a communication blackout in rural NZ or a delayed emergency response after hours.

Identifying Your Unique Hazards

The best way to start is by breaking down risks into clear categories. This structured approach ensures nothing slips through the cracks. It's most effective to look at hazards from three main angles.

- Environmental Risks: This is all about the where. Is your worker on an isolated farm with patchy reception? Navigating a construction site with trip hazards? Don't forget to factor in extreme weather, poor lighting, or public spaces.

- Task-Based Risks: These are tied directly to the job. Is your employee operating heavy machinery solo? Handling cash or valuables? Even long-distance driving on quiet rural roads falls into this category.

- People-Related Risks: This covers the individual. Does the worker have a pre-existing medical condition that could become critical without immediate help? Are they new to the role? This also includes the potential for violence or aggression from the public.

In New Zealand, we see specific challenges for lone workers, especially around personal safety, physical hazards on site, and getting help quickly in an emergency. This is particularly true for those working after hours or in isolated locations where standard mobile phones fail.

Evaluating and Mitigating Risks

Once you've listed the hazards, it's time to prioritise. For each risk, ask two questions: How likely is it to happen? And if it does, how bad would it be?

A minor papercut is a low-likelihood, low-impact risk. But a fall from height at a remote site? That’s a high-likelihood, high-severity risk that demands a robust solution like a man-down alarm and a satellite communicator. If you’re looking for practical tools, a good construction risk assessment template can be a massive help.

Your risk assessment is not a one-and-done job. It must be a living document. Review it regularly and update it anytime something changes—a new hazard, a new staff member, or an incident. This is the only way to ensure your chosen safety solutions remain effective.

Choosing the Right Safety Devices for Your Team

Once your risk assessment has identified the dangers your team faces, it’s time to equip them with the right gear. The world of lone worker technology in New Zealand ranges from smartphone apps to rugged satellite communicators. Getting this choice right is crucial—it’s not just about compliance, but a real investment in your team’s safety.

There is no one-size-fits-all solution. A real estate agent in urban Auckland has different safety needs than a forestry crew in the Coromandel. The key is to match the technology directly to the risks you've identified.

From Smartphone Apps to Satellite Messengers

The right device depends on three things: connectivity, risk level, and the specific job.

A smartphone app might seem like a cheap, easy option, but its effectiveness is entirely dependent on mobile coverage and battery life—two things that are notoriously unreliable in many parts of New Zealand.

- Smartphone Apps: Best for low-risk workers in urban areas with solid mobile reception. They handle basic check-ins and panic alerts, but are inadequate for high-risk or remote roles.

- Dedicated Lone Worker Alarms: These are purpose-built devices. They are more rugged, have a superior battery life, and many include "man down" or fall detection, which automatically sends an alert if someone is incapacitated. These are the standard for many professional roles.

- Satellite Messengers and Phones: For any team member working in remote parts of New Zealand where mobile reception is a myth, these are the only legally compliant and reliable option. They communicate directly with satellites for two-way messaging, GPS tracking, and SOS alerts from anywhere.

- Personal Locator Beacons (PLBs): A last-resort emergency device that sends a distress signal via satellite. Essential for the most isolated workers.

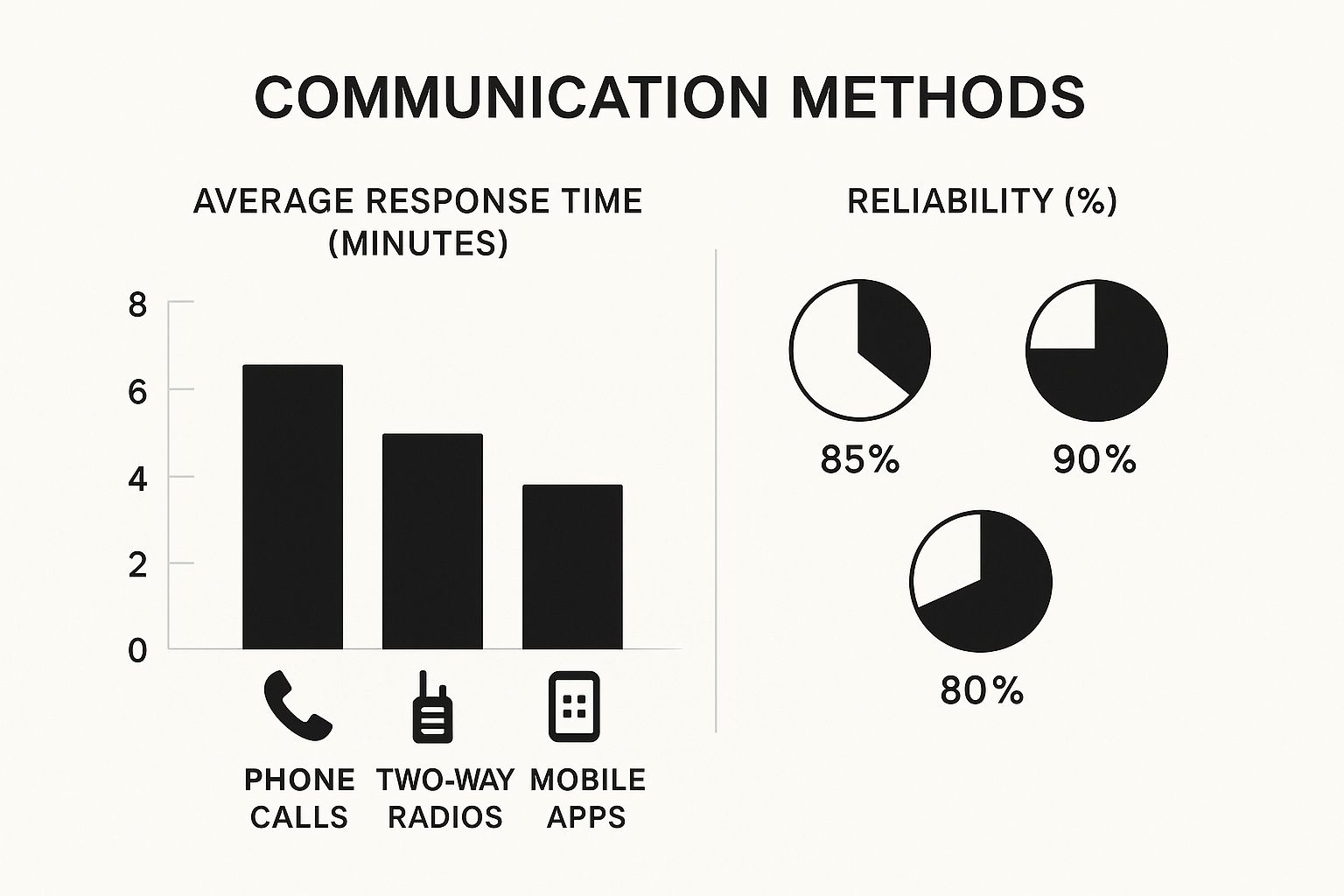

This image breaks down how different communication methods stack up in the real world.

As you can see, while mobile apps are convenient, dedicated two-way radios and other specialised gear offer far better reliability. In an emergency, reliability is everything.

Comparing Lone Worker Safety Devices

Choosing the best device can be overwhelming. This table breaks down the most common types available in New Zealand to help you match the right solution to your team's needs.

| Device Type | Best For | Key Features | Primary Limitation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Smartphone Apps | Urban, low-risk roles with consistent mobile service. | Timed check-ins, panic alerts, low initial cost. | Reliant on phone battery and cellular coverage. Not suitable for remote work. |

| Dedicated Lone Worker Alarms | High-risk roles, workers in varied environments. | "Man down" detection, long battery life, rugged design. | Higher upfront cost than an app. |

| Satellite Messengers / PLBs | Extremely remote or offshore work with no cell signal. | Global coverage, two-way messaging, SOS alerts. | Requires a clear view of the sky; subscription costs for messengers. |

| Two-Way Radios (PoC/DMR) | Teams needing instant group communication. | Push-to-talk, durable hardware, group calls. | Range can be limited without repeaters or a cellular network (for PoC). |

Ultimately, the best choice is the one that reliably covers the specific risks your workers face every single day.

Key Features to Look For

When comparing devices, a few features are non-negotiable for ensuring worker safety.

Don’t just focus on the price tag. Think about long-term reliability and the features that will make a difference when something goes wrong. The right device is an investment in your people's wellbeing, not just another expense.

Ensure the technology you choose includes:

- Accurate GPS Tracking: Knowing your worker's exact location is the first step to a fast emergency response.

- Long Battery Endurance: A dead device is useless. Look for gear that can easily last a full shift—or multiple days.

- Duress and Panic Alerts: A simple, discreet button a worker can press to signal for immediate help is a must-have.

- Automatic 'Man Down' Detection: For anyone at risk of falls, medical events, or assault, this feature is critical. It uses sensors to detect a sudden impact or lack of movement and automatically calls for help.

The connected safety market in Australia and New Zealand now covers around 490,000 users, and is expected to grow into a €75 million industry by 2029. This highlights the increasing recognition of these devices as essential business tools.

Of course, personal alarms are just one piece of the puzzle. Integrate them with wider workplace safety systems, like reliable business smoke detector solutions. And remember, clear communication isn't just for emergencies. If you need to make worksite-wide announcements, have a read of our guide on what to consider when shopping for a PA system.

Building Your Emergency Response Protocols

A panic button or a satellite messenger is only half the solution. The real strength of any lone worker safety system comes down to the human element—the clear, calm, and decisive actions your team takes when an alert is triggered. Without a solid emergency response protocol, even the best technology is just a noisemaker.

These protocols are your organisation's playbook for a crisis. They remove guesswork and panic, replacing them with a sequence of predetermined actions. This ensures a consistent, effective response every time, turning a potential disaster into a managed incident.

Establishing Communication and Check-In Procedures

Proactive communication is the foundation of a strong response plan. Regularly scheduled check-ins are a simple but powerful tool for confirming a lone worker's wellbeing. This isn't micromanagement; it's a vital safety net.

Your check-in procedure should be straightforward and tailored to the job's risk level:

- Low-Risk Roles: A community health worker in an urban area might check in at the start and end of their day.

- High-Risk Roles: A forestry surveyor in a no-signal area needs a much stricter schedule, perhaps checking in via a satellite device every two hours.

The most critical part is what happens when a check-in is missed. This is where your escalation procedure must kick in immediately.

A missed check-in must always be treated as a potential emergency until proven otherwise. Complacency is the biggest threat. You must assume the worker is in distress and needs help.

Designing a Clear Escalation Pathway

An escalation procedure is a step-by-step guide for what to do when a worker is unresponsive or triggers a duress alarm. It ensures the right people are notified in the correct order, without delay.

Here’s a practical escalation pathway:

- Immediate Contact Attempt: The monitor (a supervisor or 24/7 monitoring centre) immediately tries to contact the worker on all available channels—radio, mobile, satellite device—for a defined period, like 2-5 minutes.

- Supervisor Notification: If there's no response, the monitor contacts the worker’s direct supervisor. The supervisor can provide crucial context: Was the worker meant to be in a specific area? Do they have any known medical conditions?

- Initiate Emergency Response: If safety cannot be confirmed, the formal emergency response is launched. This means dispatching internal teams or contacting emergency services (Police, Fire, or Ambulance) with the worker’s last known GPS location and the nature of the emergency.

For team members in marine environments, this plan must also incorporate water safety protocols. Knowing how to use essential gear is vital, which is why we've put together a fact sheet on lifejackets to help clarify their role.

Ensure your plan is documented, accessible, and understood by everyone. Regular drills running through different scenarios will ensure that when a real emergency happens, your team is ready to act decisively.

Implementing Your Lone Worker Safety Program

Rolling out a safety programme isn’t just about handing out devices. Success hinges on the people using them. Your goal is to build genuine confidence and create a culture where safety is a shared responsibility, not just another top-down rule.

True buy-in starts when you explain the ‘why’. When your team understands that the check-ins and alarms are there to have their back, not to track their every move, they are far more likely to get on board. This transparency is the bedrock of a successful lone worker safety initiative.

Conducting Training That Builds Confidence

Solid training is the make-or-break element. While modern approaches like Augmented Reality for Workforce Training can offer realistic simulations, the core of good training remains practical and hands-on.

Move beyond PowerPoint slides. Your people need to get comfortable with the actual equipment they'll use daily.

- Run practical drills. Go through emergency scenarios. What’s the plan if a worker feels threatened during a site visit? What is the exact procedure if someone has a fall at a remote location?

- Practise using the alarm correctly. Show the team how to activate a duress alarm and, just as crucially, how to cancel a false one. This builds trust in the system.

- Role-play the escalation process. Walk your team through what happens when they trigger an alert. Knowing precisely who is being notified and what actions are being taken is a massive confidence booster.

The single most important outcome of training is confidence. A worker who trusts their equipment and understands the response plan is a safer worker. They’ll use the system correctly when it counts.

Fostering a Culture of Continuous Improvement

A safety programme should never be a "set and forget" exercise; it must evolve. The best source of intelligence for improving your procedures comes directly from the people on the ground—your lone workers.

Actively seek their feedback. Ask what’s working well and what’s a hassle. Are the check-in timers practical for their workflow? Have they spotted new risks on a job site that weren't in the original assessment?

This feedback loop achieves two things. First, it gives you invaluable, real-world insights to make your programme stronger. Second, it proves to your team that you value their expertise and are serious about their wellbeing. This ongoing collaboration locks in the long-term success of your lone worker safety efforts.

Common Questions About Lone Worker Safety

ven with a solid plan, questions about lone worker safety always arise. Getting clear, straightforward answers is key to building a programme that doesn't just tick a compliance box but genuinely protects your team.

We get many queries from Kiwi employers, so we've put together answers to some of the most common ones.

What Are the First Steps if We Have No Formal Lone Worker Policy?

If you have staff working alone but no formal policy, your first and most urgent step is to conduct a risk assessment. This cannot wait.

Identify every employee who works by themselves, even occasionally. Then, analyse the specific hazards they face. Under New Zealand's Health and Safety at Work Act (HSWA), not having a policy is a significant compliance risk, especially if an incident occurs.

Your first policy doesn't have to be perfect, but it must exist. At a minimum, it should detail a reliable method of communication and a non-negotiable, regular check-in procedure for every lone worker.

How Do We Protect Workers With No Mobile Reception in NZ?

For any team members in remote areas where mobile reception is patchy or non-existent—common in our agriculture, forestry, and marine sectors—you must use technology that does not rely on cellular networks. A standard mobile phone is never a sufficient primary safety device in these zones.

The legally compliant and industry-standard solutions are satellite-based devices:

- Satellite Phones: For reliable two-way voice communication.

- Satellite Messengers: For pre-set "OK" check-ins, custom texts, and critical SOS alerts.

- Personal Locator Beacons (PLBs): A last-resort device for life-threatening emergencies only.

Are Smartphone Apps Enough for Lone Worker Safety?

This is a frequent question. Smartphone apps can be a tool for low-risk workers who are always in urban areas with strong, consistent mobile coverage. They offer a low-cost way to manage basic check-ins.

However, their effectiveness is completely at the mercy of the phone's battery life, mobile service, and user diligence. For anyone in a high-risk role or working remotely in New Zealand, a dedicated lone worker device is a far more dependable and legally sound choice. These purpose-built units offer superior durability, much longer battery life, and automated alerts like 'man down' detection that an app cannot match. Your risk assessment must be your guide on whether an app is a "reasonably practicable" control for your team's specific situation.

Ready to build a safety net your team can truly rely on? The experts at Mobile Systems Limited can help you choose the right communication devices and build a robust safety programme tailored to your unique risks. Explore our solutions at https://mobilesystems.nz.